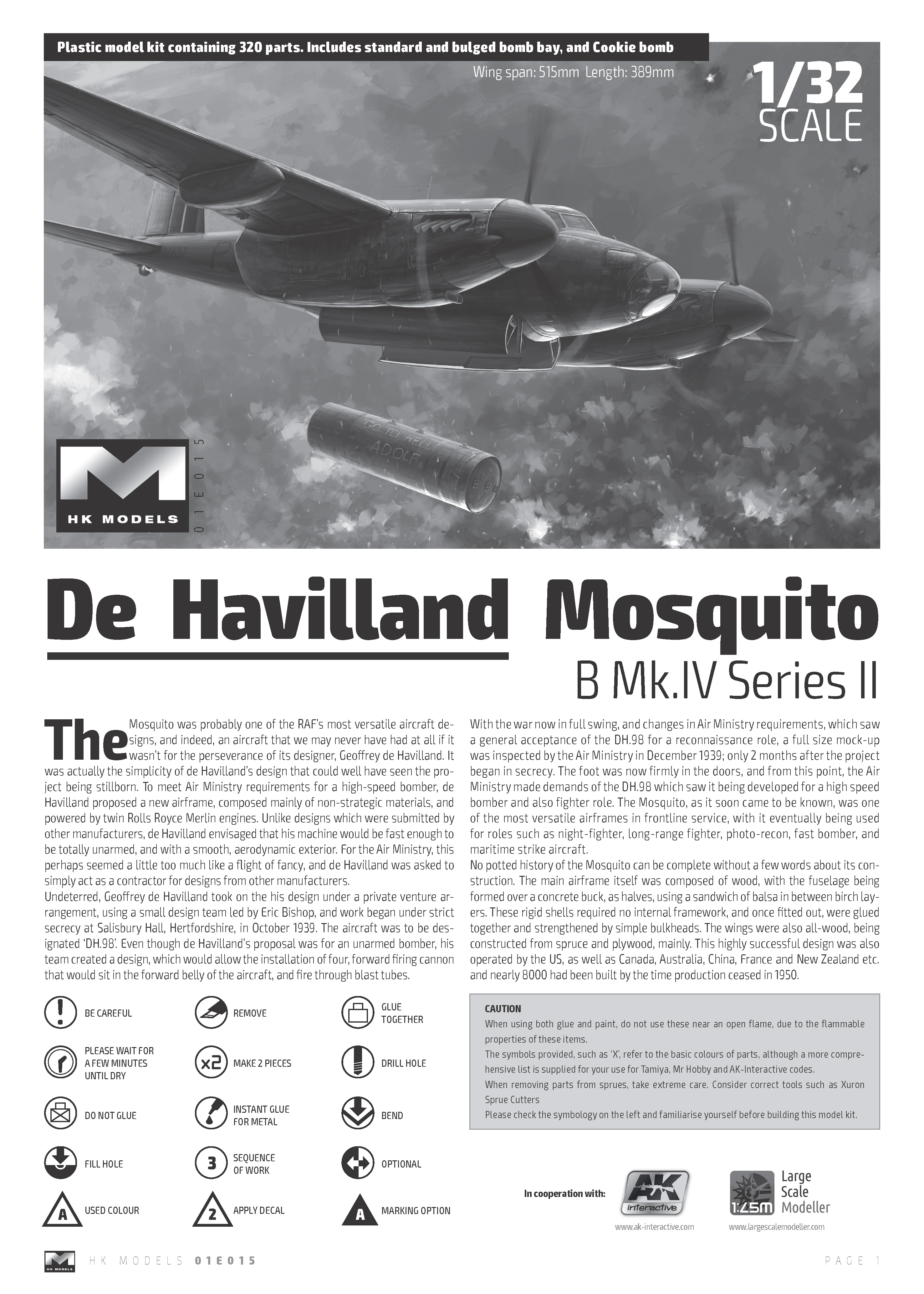

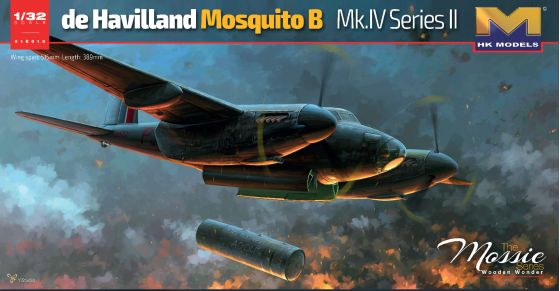

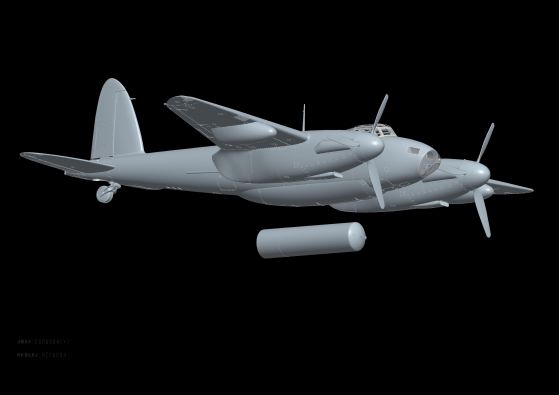

The Mosquito was probably one of the RAF’s most versatile aircraft de- signs, and indeed, an aircraft that we may never have had at all if it wasn’t for the perseverance of its designer, Geoffrey de Havilland. It

was actually the simplicity of de Havilland’s design that could well have seen the pro- ject being stillborn. To meet Air Ministry requirements for a high-speed bomber, de Havilland proposed a new airframe, composed mainly of non-strategic materials, and powered by twin Rolls Royce Merlin engines. Unlike designs which were submitted by other manufacturers, de Havilland envisaged that his machine would be fast enough to be totally unarmed, and with a smooth, aerodynamic exterior. For the Air Ministry, this perhaps seemed a little too much like a flight of fancy, and de Havilland was asked to simply act as a contractor for designs from other manufacturers.

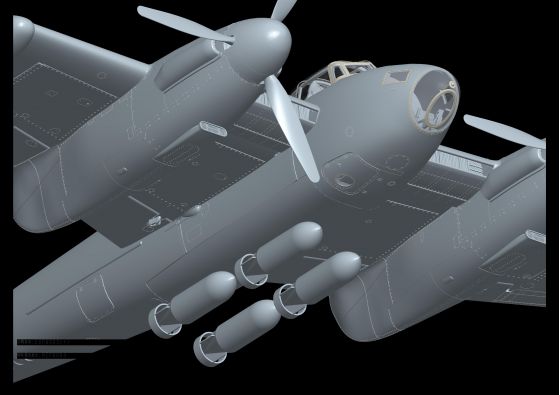

Undeterred, Geoffrey de Havilland took on the his design under a private venture ar- rangement, using a small design team led by Eric Bishop, and work began under strict secrecy at Salisbury Hall, Hertfordshire, in October 1939. The aircraft was to be des- ignated ‘DH.98’. Even though de Havilland’s proposal was for an unarmed bomber, his team created a design, which would allowthe installation offour, forward firing cannon that would sit in the forward belly ofthe aircraft, and fire through blast tubes.

With the war now in full swing, and changes in Air Ministry requirements, which saw a general acceptance of the DH.98 for a reconnaissance role, a full size mock-up was inspected by the Air Ministry in December 1939; only 2 months after the project began in secrecy. The foot was now firmly in the doors, and from this point, the Air Ministry made demands of the DH.98 which saw it being developed for a high speed bomber and also fighter role. The Mosquito, as it soon came to be known, was one of the most versatile airframes in frontline service, with it eventually being used for roles such as night-fighter, long-range fighter, photo-recon, fast bomber, and maritime strike aircraft.

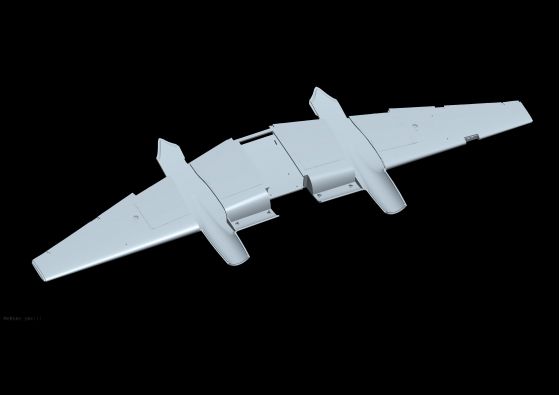

No potted history of the Mosquito can be complete without a few words about its con- struction. The main airframe itself was composed of wood, with the fuselage being formed over a concrete buck, as halves, using a sandwich ofbalsa in between birch lay- ers. These rigid shells required no internal framework, and once fitted out, were glued together and strengthened by simple bulkheads. The wings were also all-wood, being constructed from spruce and plywood, mainly. This highly successful design was also operated by the US, as well as Canada, Australia, China, France and New Zealand etc. and nearly 8000 had been built by the time production ceased in 1950.